Have you ever built a piece of IKEA furniture, or put together a LEGO set, by following the instructions closely and only at the end realized at some point you didn’t quite follow them correctly? The final result might be close to what was intended, but there’s a nagging thought that maybe, just maybe, it’s not as rock steady or functional as it could have been.

Internet protocol specifications are instructions designed for engineers to build things. Protocol designers take great care to ensure the documents they produce are clear. The standardization process gathers consensus and review from experts in the field, to further ensure document quality. Any reasonably skilled engineer should be able to take a specification and produce a performant, reliable, and secure implementation. The Internet is central to everyone’s lives, and we depend on these implementations. Any deviations from the specification can put us at risk. For example, mishandling of malformed requests can allow attacks such as request smuggling.

h3i is a binary command line tool and Rust library designed for low-level testing and debugging of HTTP/3, which runs over QUIC. h3i is free and open source as part of Cloudflare’s quiche project. In this post we’ll explain the motivation behind developing h3i, how we use it to help develop robust and safe standards-compliant software and production systems, and how you can similarly use it to test your own software or services. If you just want to jump into how to use h3i, go to the h3i command line tool section.

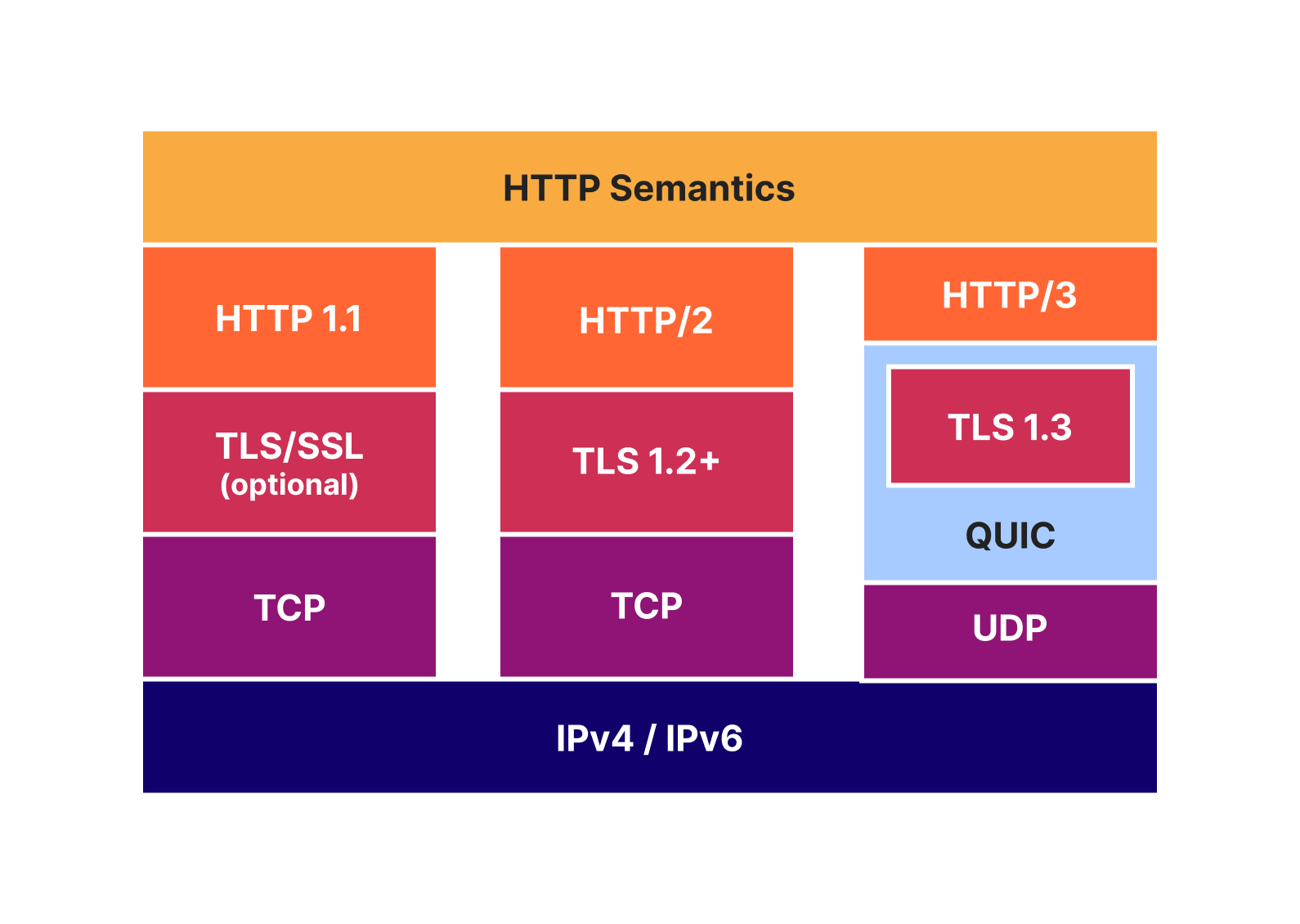

QUIC is a secure-by-default transport protocol that provides performance advantages compared to TCP and TLS via a more efficient handshake, along with stream multiplexing that provides head-of-line blocking avoidance. HTTP/3 is an application protocol that maps HTTP semantics to QUIC, such as defining how HTTP requests and responses are assigned to individual QUIC streams.

Cloudflare has supported QUIC on our global network in some shape or form since 2018. We started while the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) was earnestly standardizing the protocol, working through early iterations and using interoperability testing and experience to help provide feedback for the standards process. We launched support for QUIC version 1 and HTTP/3 as soon as RFC 9000 (and its accompanying specifications) were published in 2021.

We work on the Protocols team, who own the ingress proxy into the Cloudflare network. This is essentially Cloudflare’s “front door” — HTTP requests that come to Cloudflare from the Internet pass through us first. The majority of requests are passed onwards to things like rulesets, workers, caches, or a customer origin. However, you might be surprised that many requests don’t ever make it that far because they are, in some way, invalid or malformed. Servers listening on the Internet have to be robust to traffic that is not RFC compliant, whether caused by accident or malicious intent.

The Protocols team actively participates in IETF standardization work and has also helped build and maintain other Cloudflare services that leverage quiche for QUIC and HTTP/3, from the proxies that help iCloud Private Relay via MASQUE proxying, to replacing WARP’s use of Wireguard with MASQUE, and beyond.

Throughout all of these different use cases, it is important for us to extensively test all aspects of the protocols. A deep dive into protocol details is a blog post (or three) in its own right. So let’s take a thin slice across HTTP to help illustrate the concepts.

HTTP Semantics are common to all versions of HTTP — the overall architecture, terminology, and protocol aspects such as request and response messages, methods, status codes, header and trailer fields, message content, and much more. Each individual HTTP version defines how semantics are transformed into a “wire format” for exchange over the Internet. You can read more about HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2 in some of our previous blog posts.

With HTTP/3, HTTP request and response messages are split into a series of binary frames. HEADERS frames carry a representation of HTTP metadata (method, path, status code, field lines). The payload of the frame is the encoded QPACK compression output. DATA frames carry HTTP content (aka “message body”). In order to exchange these frames, HTTP/3 relies on QUIC streams. These provide an ordered and reliable byte stream and each have an identifier (ID) that is unique within the scope of a connection. There are four different stream types, denominated by the two least significant bits of the ID.

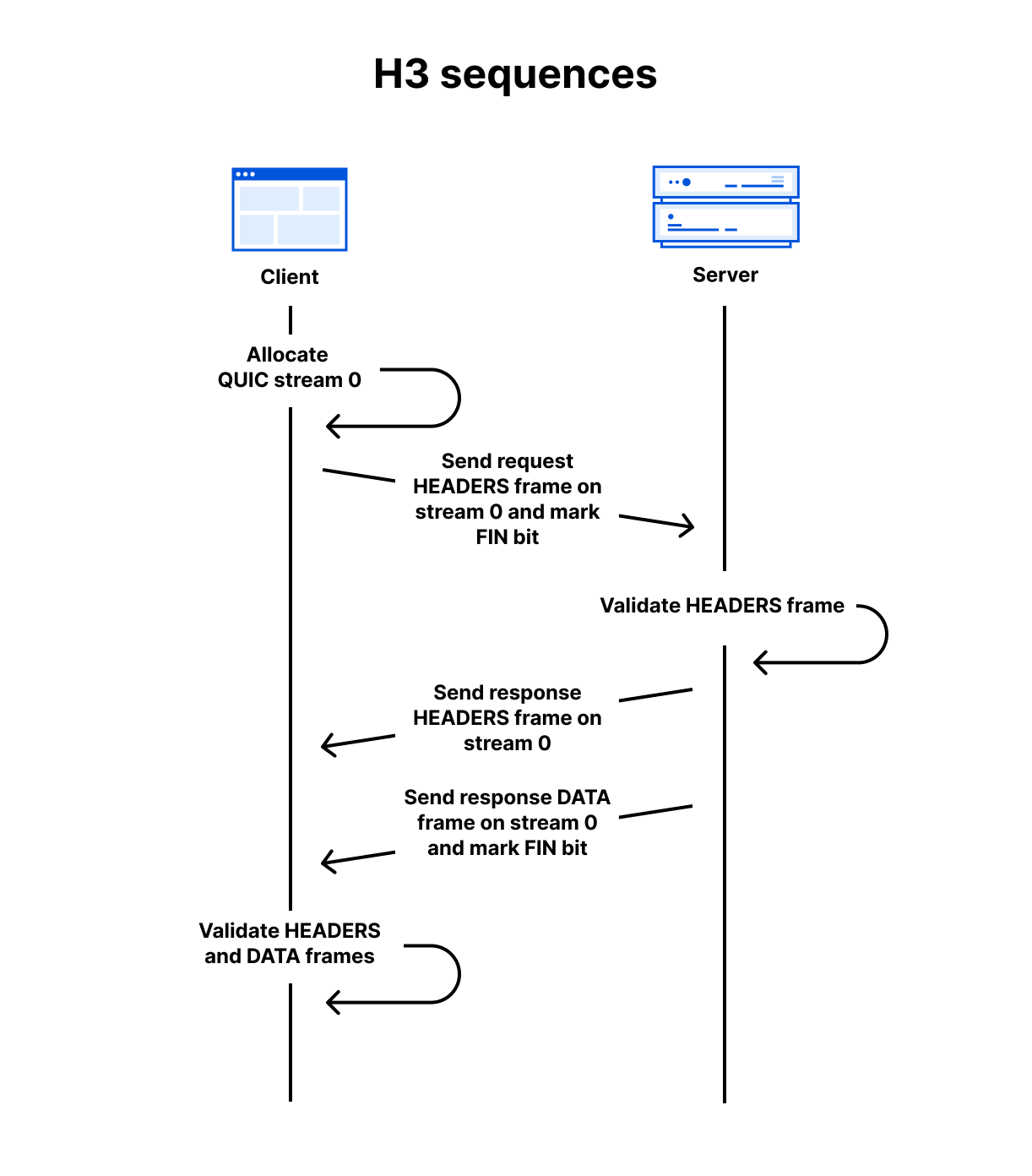

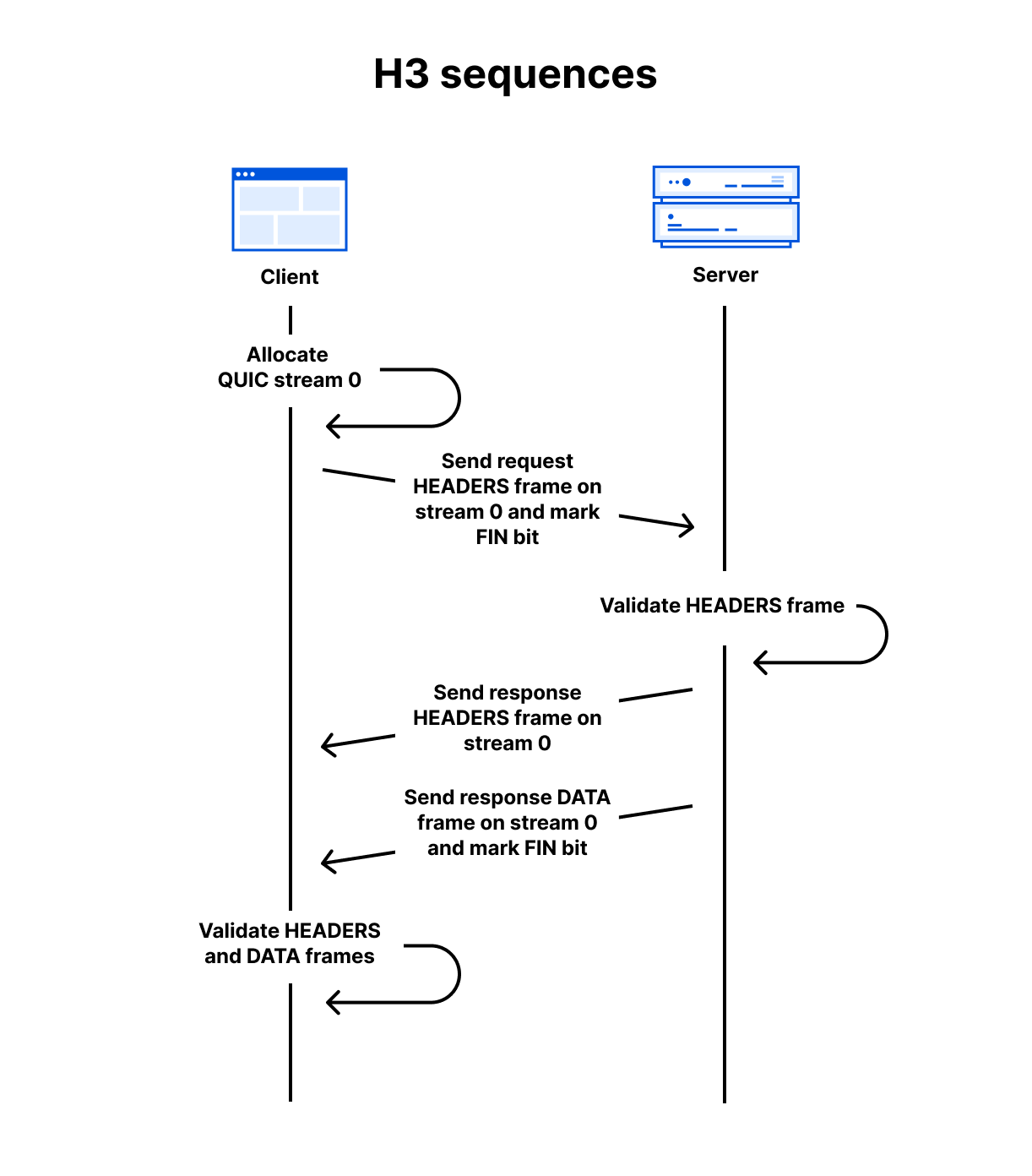

As a simple example, assuming a QUIC connection has already been established, a client can make a GET request and receive a 200 OK response with an HTML body using the follow sequence:

-

Client allocates the first available client-initiated bidirectional QUIC stream. (The IDs start at 0, then 4, 8, 12 and so on)

-

Client sends the request HEADERS frame on the stream and sets the stream’s FIN bit to mark the end of stream.

-

Server receives the request HEADERS frame and validates it against RFC 9114 rules. If accepted, it processes the request and prepares the response.

-

Server sends the response HEADERS frame on the same stream.

-

Server sends the response DATA frame on the same stream and sets the FIN bit.

-

Client receives the response frames and validates them. If accepted, the content is presented to the user.

At the QUIC layer, stream data is split into STREAM frames, which are sent in QUIC packets over UDP. QUIC deals with any loss detection and recovery, helping to ensure stream data is reliable. The layer cake diagram below provides a handy comparison of how HTTP/1.1, HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 use TCP, UDP and IP.

The Protocols team has a diverse set of automated test tools that exercise our ingress proxy software in order to ensure it can stand up to the deluge that the Internet can throw at it. Just like a bouncer at a nightclub front door, we need to prevent as much bad traffic as possible before it gets inside and potentially causes damage.

HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 share several concepts. When we started developing early HTTP/3 support, we’d already learned a lot from production experience with HTTP/2. While HTTP/2 addressed many issues with HTTP/1.1 (especially problems like request smuggling, caused by its ASCII-based message delineation), HTTP/2 also added complexity and new avenues for attack. Security is an ongoing process, and the Protocols team continually hardens our software and systems to threats. For example, mitigating the range of denial-of-service attacks identified by Netflix in 2019, or the HTTP/2 Rapid Reset attacks of 2023.

For testing HTTP/2, we rely on the Python Requests library for testing conventional HTTP exchanges. However, that mostly only exercises HEADERS and DATA frames. There are eight other frame types and a plethora of ways that they can interact (hence the new attack vectors mentioned above). In order to get full testing coverage, we have to break down into the lower layer h2 library, which allows exact frame-by-frame control. However, even that is not always enough. Libraries tend to want to follow the RFC rules and prevent their users from doing “the wrong thing”. This is entirely logical for most purposes. For our needs though, we need to take off the safety guards just like any potential attackers might do. We have a few cases where the best way to exercise certain traffic patterns is to handcraft HTTP/2 frames in a hex editor, store that as binary, and replay it with a tool such as OpenSSL s_client.

We knew we’d need similar testing approaches for HTTP/3. However, when we started in 2018, there weren’t many other suitable client implementations. The rate of iteration on the specifications also meant it was hard to always keep in sync. So we built tests on quiche, using a mix of our quiche-client and http3_test. Over time, the python library aioquic has matured, and we have used it to add a range of lower-layer tests that break or bend HTTP/3 rules, in order to prove our proxies are robust.

Finally, we would be remiss not to mention that all the tests in our ingress proxy are in addition to the suite of over 500 integration tests that run on the quiche project itself.

While we are happy with the coverage of our current tests, the smorgasbord of test tools makes it hard to know what to reach for when adding new tests. For example, we’ve had cases where aioquic’s safety guards prevent us from doing something, and it has needed a patch or workaround. This sort of thing requires a time investment just to debug/develop the tests.

We believe it shouldn’t take a protocol or code expert to develop what are often very simple to describe tests. While it is important to provide guide rails for the majority of conventional use cases, it is also important to provide accessible methods for taking them off.

Let’s consider a simple example. In HTTP/3 there is something called the control stream. It’s used to exchange frames such as SETTINGS, which affect the HTTP/3 connection. RFC 9114 Section 6.2.1 states:

Each side MUST initiate a single control stream at the beginning of the connection and send its SETTINGS frame as the first frame on this stream. If the first frame of the control stream is any other frame type, this MUST be treated as a connection error of type H3_MISSING_SETTINGS. Only one control stream per peer is permitted; receipt of a second stream claiming to be a control stream MUST be treated as a connection error of type H3_STREAM_CREATION_ERROR. The sender MUST NOT close the control stream, and the receiver MUST NOT request that the sender close the control stream. If either control stream is closed at any point, this MUST be treated as a connection error of type H3_CLOSED_CRITICAL_STREAM. Connection errors are described in Section 8.

There are many tests we can conjure up just from that paragraph:

-

Send a non-SETTINGS frame as the first frame on the control stream.

-

Open two control streams.

-

Open a control stream and then close it with a FIN bit.

-

Open a control stream and then reset it with a RESET_STREAM QUIC frame.

-

Wait for the peer to open a control stream and then ask for it to be reset with a STOP_SENDING QUIC frame.

All of the above actions should cause a remote peer that has implemented the RFC properly to close the connection. Therefore, it is not in the interest of the local client or server applications to ever do these actions.

Many QUIC and HTTP/3 implementations are developed as libraries that are integrated into client or server applications. There may be an extensive set of unit or integration tests of the library checking RFC rules. However, it is also important to run the same tests on the integrated assembly of library and application, since it’s all too common that an unhandled/mishandled library error can cascade to cause issues in upper layers. For instance, the HTTP/2 Rapid Reset attacks affected Cloudflare due to their impact on how one service spoke to another.

We’ve developed h3i, a command line tool and library, to make testing more accessible and maintainable for all. We started with a client that can exercise servers, since that’s what our focus has been. Future developments could support the opposite, a server that behaves in unusual ways in order to exercise clients.

Note: h3i is not intended to be a production client! Its flexibility may cause issues that are not observed in other production-oriented clients. It is also not intended to be used for any type of performance testing and measurement.

The primary purpose of the h3i command line tool is quick low-level debugging and exploratory testing. Rather than worrying about writing code or a test script, users can quickly run an ad-hoc client test against a target, guided by interactive prompts.

In the simplest case, you can think of h3i a bit like curl but with access to some extra HTTP/3 parameters. In the example below, we issue a request to https://cloudflare-quic.com/ and receive a response.

Walking through a simple GET with h3i step-by-step:

-

Grab a copy of the h3i binary either by running

cargo install h3ior cloning the quiche source repo at https://github.com/cloudflare/quiche/. Both methods assume you have some familiarity with Rust and Cargo. See the cargo documentation for more information.-

cargo installwill place the binary on your path, so you can then just run it by executingh3i. -

If running from source, navigate to the quiche/h3i directory and then use

cargo run.

-

-

Run the binary and provide the name and port of the target server. If the port is omitted, the default value 443 is assumed. E.g,

cargo run cloudflare-quic.com -

h3i then enters the action prompting phase. A series of one or more HTTP/3 actions can be queued up, such as sending frames, opening or terminating streams, or waiting on data from the server. The full set of options is documented in the readme.

-

The prompting interface adapts to keyboard inputs and supports tab completion.

-

In the example above, the

headersaction is selected, which walks through populating the fields in a HEADERS frame. It includes mandatory fields from RFC 9114 for convenience. If a test requires omitting these, theheaders_no_pseudocan be used instead.

-

-

The

commitprompt choice finalizes the action list and moves to the connection phase. h3i initiates a QUIC connection to the server identified in step 2. Once connected, actions are executed in order. -

By default, h3i reports some limited information about the frames the server sent. To get more detailed information, the

RUST_LOGenvironment can be set with eitherdebugortracelevels.

It can be fun to play around with the h3i command line tool to see how different servers respond to different combinations or sequences of actions. Occasionally, you’ll find a certain set that you want to run over and over again, or share with a friend or colleague. Having to manually enter the prompts repeatedly, or share screenshots of the h3i input can turn tedious. Fortunately, h3i records all the actions in a log file by default — the file path is printed immediately after h3i starts. The format of this file is based on qlog, an in-progress standard in development at the IETF for network protocol logging. It’s a perfect fit for our low-level needs.

Here’s an example h3i qlog file:

{"qlog_version":"0.3","qlog_format":"JSON-SEQ","title":"h3i","description":"h3i","trace":{"vantage_point":{"type":"client"},"title":"h3i","description":"h3i","configuration":{"time_offset":0.0}}}

{

"time": 0.172783,

"name": "http:frame_created",

"data": {

"stream_id": 0,

"frame": {

"frame_type": "headers",

"headers": [

{

"name": ":method",

"value": "GET"

},

{

"name": ":authority",

"value": "cloudflare-quic.com"

},

{

"name": ":path",

"value": "/"

},

{

"name": ":scheme",

"value": "https"

},

{

"name": "user-agent",

"value": "h3i"

}

]

}

},

"fin_stream": true

}h3i logs can be replayed using the --qlog-input option. You can change the target server host and port, and keep all the same actions. However, most servers will validate the :authority pseudo-header or Host header contained in a HEADERS frame. The –replay-host-override option allows changing these fields without needing to modify the file by hand.

And yes, qlog files are human-readable text in the JSON-SEQ format. So you can also just write these by hand in the first place if you like! However, if you’re going to start writing things, maybe Rust is your preferred option…

In our previous example, we just sent a valid request so there wasn’t anything interesting to observe. Where h3i really shines is in generating traffic that isn’t RFC compliant, such as malformed HTTP messages, invalid frame sequences, or other actions on streams. This helps determine if a server is acting robustly and defensively.

Let’s explore this more with an example of HTTP content-length mismatch. RFC 9114 section 4.1.2 specifies:

A request or response that is defined as having content when it contains a Content-Length header field (Section 8.6 of [HTTP]) is malformed if the value of the Content-Length header field does not equal the sum of the DATA frame lengths received. A response that is defined as never having content, even when a Content-Length is present, can have a non-zero Content-Length header field even though no content is included in DATA frames.

Intermediaries that process HTTP requests or responses (i.e., any intermediary not acting as a tunnel) MUST NOT forward a malformed request or response. Malformed requests or responses that are detected MUST be treated as a stream error of type H3_MESSAGE_ERROR.

For malformed requests, a server MAY send an HTTP response indicating the error prior to closing or resetting the stream.

There are good reasons that the RFC is so strict about handling mismatched content lengths. They can be a vector for desynchronization attacks (similar to request smuggling), especially when a proxy is converting inbound HTTP/3 to outbound HTTP/1.1.

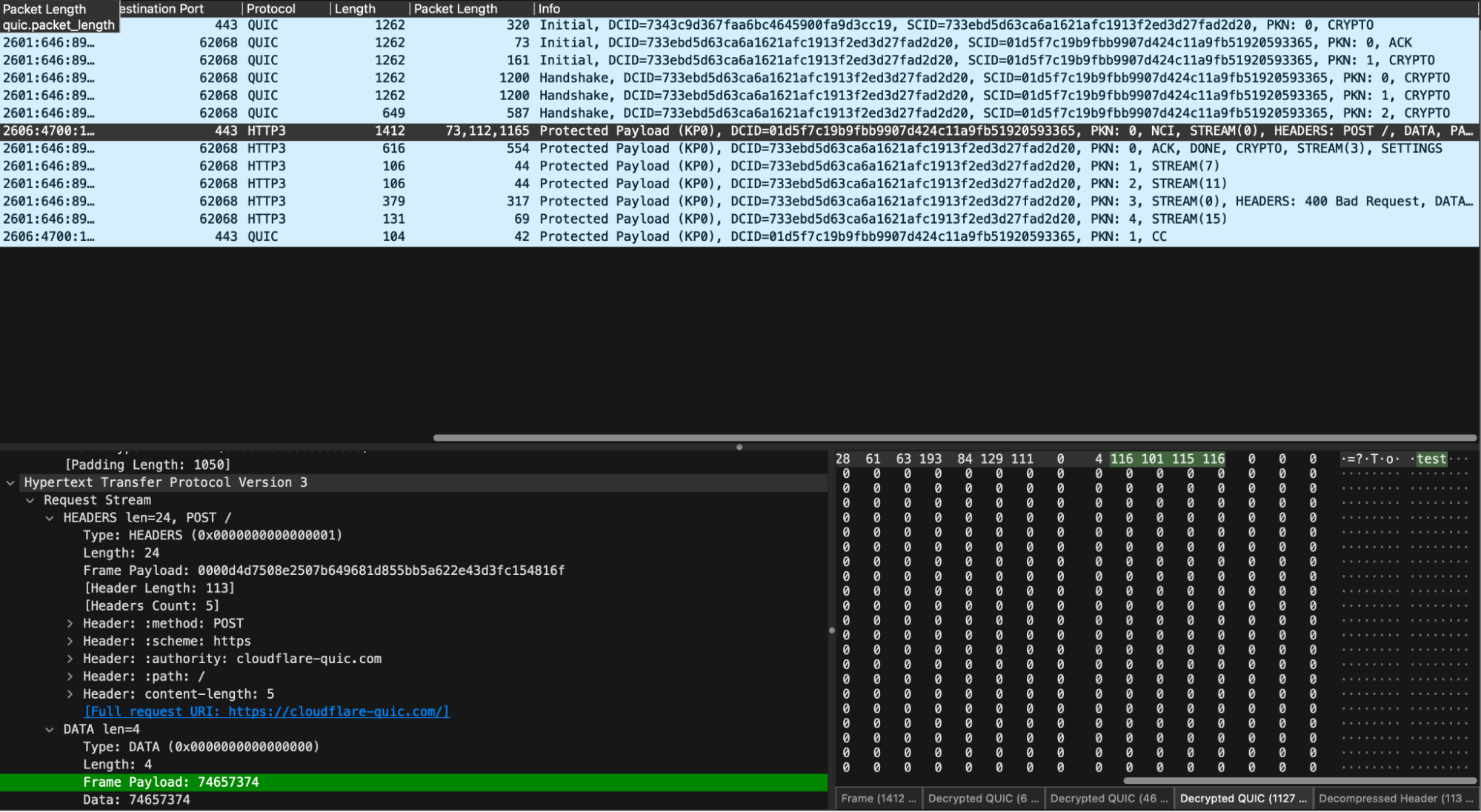

We’ve provided an example of how to use the h3i Rust library to write a tailor-made test client that sends a mismatched content length request. It sends a Content-Length header of 5, but its body payload is “test”, which is only 4 bytes. It then waits for the server to respond, after which it explicitly closes the connection by sending a QUIC CONNECTION_CLOSE frame.

When running low-level tests, it can be interesting to also take a packet capture (pcap) and observe what is happening on the wire. Since QUIC is an encrypted transport, we’ll need to use the SSLKEYLOG environment variable to capture the session keys so that tools like Wireshark can decrypt and dissect.

To follow along at home, clone a copy of the quiche repository, start a packet capture on the appropriate network interface and then run:

cd quiche/h3i

SSLKEYLOGFILE="h3i-example.keys" cargo run --example content_length_mismatchIn our decrypted capture, we see the expected sequence of handshake, request, response, and then closure.

The example is a simple binary app with a main() entry point. Let’s survey the key elements.

First, we set up an h3i configuration to a target server:

let config = Config::new()

.with_host_port("cloudflare-quic.com".to_string())

.with_idle_timeout(2000)

.build()

.unwrap();The idle timeout is a QUIC concept which tells each endpoint when it should close the connection if the connection has been idle. This prevents endpoints from spinning idly if the peer hasn’t closed the connection. h3i’s default is 30 seconds, which can be too long for tests, so we set ours to 2 seconds here.

Next, we define a set of request headers and encode them with QPACK compression, ready to put in a HEADERS frame. Note that h3i does provide a send_headers_frame helper method which does this for you, but the example does it manually for clarity:

let headers = vec![

Header::new(b":method", b"POST"),

Header::new(b":scheme", b"https"),

Header::new(b":authority", b"cloudflare-quic.com"),

Header::new(b":path", b"/"),

// We say that we're going to send a body with 5 bytes...

Header::new(b"content-length", b"5"),

];

let header_block = encode_header_block(&headers).unwrap();Then, we define the set of h3i actions that we want to execute in order: send HEADERS, send a too-short DATA frame, wait for the server’s HEADERS, then close the connection.

let actions = vec![

Action::SendHeadersFrame {

stream_id: STREAM_ID,

fin_stream: false,

headers,

frame: Frame::Headers { header_block },

},

Action::SendFrame {

stream_id: STREAM_ID,

fin_stream: true,

frame: Frame::Data {

// ...but, in actuality, we only send 4 bytes. This should yield a

// 400 Bad Request response from an RFC-compliant

// server: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc9114#section-4.1.2-3

payload: b"test".to_vec(),

},

},

Action::Wait {

wait_type: WaitType::StreamEvent(StreamEvent {

stream_id: STREAM_ID,

event_type: StreamEventType::Headers,

}),

},

Action::ConnectionClose {

error: quiche::ConnectionError {

is_app: true,

error_code: quiche::h3::WireErrorCode::NoError as u64,

reason: vec![],

},

},

];Finally, we’ll set things in motion with connect(), which sets up the QUIC connection, executes the actions list and collects the summary.

let summary =

sync_client::connect(config, &actions).expect("connection failed");

println!(

"=== received connection summary! ===nn{}",

serde_json::to_string_pretty(&summary).unwrap_or_else(|e| e.to_string())

);ConnectionSummary provides data about the connection, including the frames h3i received, details about why the connection closed, and connection statistics. The example prints the summary out. However, you can programmatically check it. We do this to write our own internal automation tests.

If you’re running the example, it should print something like the following:

=== received connection summary! ===

{

"stream_map": {

"0": [

{

"UNKNOWN": {

"raw_type": 2471591231244749708,

"payload": ""

}

},

{

"UNKNOWN": {

"raw_type": 2031803309763646295,

"payload": "4752454153452069732074686520776f7264"

}

},

{

"enriched_headers": {

"header_block_len": 75,

"headers": [

{

"name": ":status",

"value": "400"

},

{

"name": "server",

"value": "cloudflare"

},

{

"name": "date",

"value": "Sat, 07 Dec 2024 00:34:12 GMT"

},

{

"name": "content-type",

"value": "text/html"

},

{

"name": "content-length",

"value": "155"

},

{

"name": "cf-ray",

"value": "8ee06dbe2923fa17-ORD"

}

]

}

},

{

"DATA": {

"payload_len": 104

}

},

{

"DATA": {

"payload_len": 51

}

}

]

},

"stats": {

"recv": 10,

"sent": 5,

"lost": 0,

"retrans": 0,

"sent_bytes": 1712,

"recv_bytes": 4178,

"lost_bytes": 0,

"stream_retrans_bytes": 0,

"paths_count": 1,

"reset_stream_count_local": 0,

"stopped_stream_count_local": 0,

"reset_stream_count_remote": 0,

"stopped_stream_count_remote": 0,

"path_challenge_rx_count": 0

},

"path_stats": [

{

"local_addr": "0.0.0.0:64418",

"peer_addr": "104.18.29.7:443",

"active": true,

"recv": 10,

"sent": 5,

"lost": 0,

"retrans": 0,

"rtt": 0.008140072,

"min_rtt": 0.004645536,

"rttvar": 0.004238173,

"cwnd": 13500,

"sent_bytes": 1712,

"recv_bytes": 4178,

"lost_bytes": 0,

"stream_retrans_bytes": 0,

"pmtu": 1350,

"delivery_rate": 247720

}

],

"error": {

"local_error": {

"is_app": true,

"error_code": 256,

"reason": ""

},

"timed_out": false

}

}

Let’s walk through the output. Up first is the StreamMap, which is a record of all frames received on each stream. We can see that we received 5 frames on stream 0: 2 UNKNOWNs, one EnrichedHeaders frame, and two DATA frames.

The UNKNOWN frames are extension frames that are unknown to h3i; the server under test is sending what are known as GREASE frames to help exercise the protocol and ensure clients are not erroring when they receive something unexpected per RFC 9114 requirements.

The EnrichedHeaders frame is essentially an HTTP/3 HEADERS frame, but with some small helpers, like one to get the response status code. The server under test sent a 400 as expected.

The DATA frames carry response body bytes. In this case, the body is the HTML required to render the Cloudflare Bad Request page (you can peek at the HTML yourself in Wireshark). We chose to omit the raw bytes from the ConnectionSummary since they may not be representable safely as text. A future improvement could be to encode the bytes in base64 or hex, in order to support tests that need to check response content.

We believe h3i is a great library for building automated tests on. You can take the above example and modify it to fit within various types of (continuous) integration tests.

We outlined earlier how the Protocols team HTTP/3 testing has organically grown to use three different frameworks. Even within those, we still didn’t have much flexibility and ease of use. Over the last year we’ve been building h3i itself and reimplementing our suite of ingress proxy test cases using the Rust library. This has helped us improve test coverage with a range of new tests not previously possible. It also surprisingly identified some problems with the old tests, particularly for some edge cases where it wasn’t clear how the old test code implementation was running under the hood.

RFC 1025 was published in 1987. Authored by Jon Postel, it discusses bake offs:

In the early days of the development of TCP and IP, when there were very few implementations and the specifications were still evolving, the only way to determine if an implementation was “correct” was to test it against other implementations and argue that the results showed your own implementation to have done the right thing. These tests and discussions could, in those early days, as likely change the specification as change the implementation.

There were a few times when this testing was focused, bringing together all known implementations and running through a set of tests in hopes of demonstrating the N squared connectivity and correct implementation of the various tricky cases. These events were called “Bake Offs”.

While nearly 4 decades old, the concept of exercising Internet protocol implementations and seeing how they compare to the specification still holds true. The QUIC WG made heavy use of interoperability testing through its standardization process. We started off sitting in a room and running tests manually by hand (or with some help from scripts). Then Marten Seemann developed the QUIC Interop Runner, which runs regular automated testing and collects and renders all the results. This has proven to be incredibly useful.

The state of HTTP/3 interoperability testing is not quite as mature. Although there are tools such as Kazu Yamamoto’s excellent h3spec (in Haskell) for testing conformance, there isn’t a similar continuous integration process of collection and rendering of results. While h3i shares similarities with h3spec, we felt it important to focus on the framework capabilities rather than creating a corpus of tests and assertions. Cloudflare is a big fan of Rust and as several teams move to Rust-based proxies, having a consistent ecosystem provides advantages (such as developer velocity).

We certainly feel there is a great opportunity for continued collaboration and cross-pollination between projects in the QUIC and HTTP space. For example, h3i might provide a suitable basis to build another tool (or set of scripts) to run bake offs or interop tests. Perhaps it even makes sense to have a common collection of test cases owned by the community, that can be specialized to the most appropriate or preferred tooling. This topic was recently presented at the HTTP Workshop 2024 by Mohammed Al-Sahaf, and it excites us to see new potential directions of testing improvements.

When using any tools or methods for protocol testing, we encourage responsible handling of security-related matters. If you believe you may have identified a vulnerability in an IETF Internet protocol itself, please follow the IETF’s reporting guidance. If you believe you may have discovered an implementation vulnerability in a product, open source project, or service using QUIC or HTTP, then you should report these directly to the responsible party. Implementers or operators often provide their own publicly-available guidance and contact details to send reports. For example, the Cloudflare quiche security policy is available in the Security tab of the GitHub repository.

Cloudflare takes testing very seriously. While h3i has a limited feature set as a test HTTP/3 client, we believe it provides a strong framework that can be extended to a wider range of different cases and different protocols. For example, we’d like to add support for low-level HTTP/2.

We’ve designed h3i to integrate into a wide range of testing methodologies, from manual ad-hoc testing, to native Rust tests, to conformance testbenches built with scripting languages. We’ve had great success migrating our existing zoo of test tools to a single one that is more accessible and easier to maintain.

Now that you’ve read about h3i’s capabilities, it’s left as an exercise to the reader to go back to the example of HTTP/3 control streams and consider how you could write tests to exercise a server.

We encourage the community to experiment with h3i and provide feedback, and propose ideas or contributions to the GitHub repository as issues or Pull Requests.